|

The Lithographs

Lithographs of John C. Menihan

of John C. Menihan

by

Ron Netsky

One

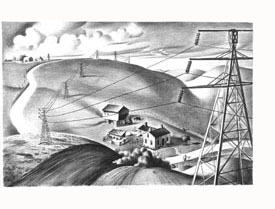

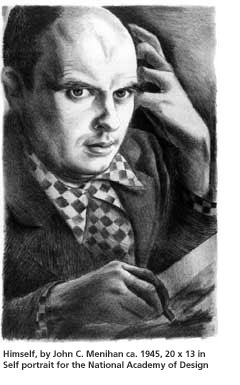

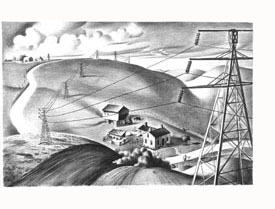

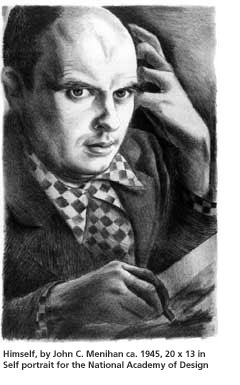

of the most important chapters in the long and varied artistic career

of John C. Menihan (1908-1992) was his two-decade-long involvement

with lithography. From the early 1930s to the early 1950s, Menihan,

who lived in Rochester, New York, created more than 100 lithographs

which constitute a significant body of prints that rivals the finest

work of regionalist and American Scene printmakers.

Although

Menihan's expressive realism may draw comparisons with the work

of Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, his style has distinctive

qualities that set him apart from other artists of his generation.

His fascination with rural and urban life, recreation and industry,

and people in their environments imbues his prints with an authenticity

seldom matched. And his technical knowledge of the medium gleaned

from his mentor, master lithographer Bolton Brown, is equal to that

of the period's greatest printmakers. Although

Menihan's expressive realism may draw comparisons with the work

of Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, his style has distinctive

qualities that set him apart from other artists of his generation.

His fascination with rural and urban life, recreation and industry,

and people in their environments imbues his prints with an authenticity

seldom matched. And his technical knowledge of the medium gleaned

from his mentor, master lithographer Bolton Brown, is equal to that

of the period's greatest printmakers.

Menihan's

first encounter with lithography came in the late 1920s while he

was attending the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of

Business. Exhibitions he attended in Philadelphia galleries Menihan's

first encounter with lithography came in the late 1920s while he

was attending the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of

Business. Exhibitions he attended in Philadelphia galleries  by

Joseph Pennell, James A. McNeill Whistler and Robert Riggs spurred

his interest in the medium. by

Joseph Pennell, James A. McNeill Whistler and Robert Riggs spurred

his interest in the medium.

Menihan

found his way to Brown's studio at the urging of Walter Cassebeer,

a Rochester architect who also made lithographs. Menihan had seen

an exhibition of Cassebeer's lithographs in the early 1930s and

asked him for advice on getting started in the medium. Cassebeer

recommended Brown's recently published book Lithography for Artists,

and once he acquired it, Menihan was anxious to study with its author.

Brown's name was already familiar to Menihan because he had received

a book of lithographs by George Bellows (many of which were printed

by Brown) for a graduation present. Menihan

found his way to Brown's studio at the urging of Walter Cassebeer,

a Rochester architect who also made lithographs. Menihan had seen

an exhibition of Cassebeer's lithographs in the early 1930s and

asked him for advice on getting started in the medium. Cassebeer

recommended Brown's recently published book Lithography for Artists,

and once he acquired it, Menihan was anxious to study with its author.

Brown's name was already familiar to Menihan because he had received

a book of lithographs by George Bellows (many of which were printed

by Brown) for a graduation present.

In

Menihan's 1940 application for a National Endowment for the Arts

grant he wrote that his approach to lithography was "mainly based

on a way of thinking acquired at the feet of Bolton Brown." In

Menihan's 1940 application for a National Endowment for the Arts

grant he wrote that his approach to lithography was "mainly based

on a way of thinking acquired at the feet of Bolton Brown."

"...the richness of my association with him is indescribable. He

was unsurpassed as a technician and inspiring as a man, demanding

perfection and capable of instilling his ideals in others willing

to hear him. He was truly the only important influence on my life

as an artist." "...the richness of my association with him is indescribable. He

was unsurpassed as a technician and inspiring as a man, demanding

perfection and capable of instilling his ideals in others willing

to hear him. He was truly the only important influence on my life

as an artist."

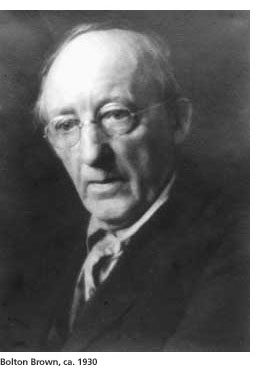

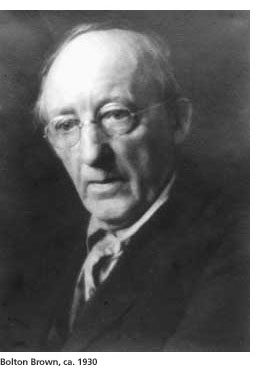

Menihan

was at the beginning of his career when he encountered Brown, who

was near the end of his. Brown (1864-1936) had been a founder of

Byrdcliffe, the artists' colony in Woodstock, NY and the printer

of more than 100 lithographs by Bellows. Although Brown was himself

an accomplished painter Menihan

was at the beginning of his career when he encountered Brown, who

was near the end of his. Brown (1864-1936) had been a founder of

Byrdcliffe, the artists' colony in Woodstock, NY and the printer

of more than 100 lithographs by Bellows. Although Brown was himself

an accomplished painter  and

lithographer, he was not adequately recognized for his significant

contributions to lithography at the time. (Brown's work began to

attract interest in the late 1970s.) and

lithographer, he was not adequately recognized for his significant

contributions to lithography at the time. (Brown's work began to

attract interest in the late 1970s.)

The

lack of attention to his work during his lifetime was a major source

of Brown's bitterness about the art world in 1934 when Menihan became

his last student. Brown had witnessed the ascent of men like Joseph

Pennell, who knew very little about the complex process of lithography,

while his own career languished. He nevertheless created hundreds

of delicate, technically unsurpassed lithographs. He also undertook

more experimentation in the chemistry of lithography and the making

of lithographic crayons than anyone in the history of the medium.

When Menihan studied with Brown in 1934 and 1935, it is no exaggeration

to say that he was under the tutelage of the world's foremost expert

in lithography. The

lack of attention to his work during his lifetime was a major source

of Brown's bitterness about the art world in 1934 when Menihan became

his last student. Brown had witnessed the ascent of men like Joseph

Pennell, who knew very little about the complex process of lithography,

while his own career languished. He nevertheless created hundreds

of delicate, technically unsurpassed lithographs. He also undertook

more experimentation in the chemistry of lithography and the making

of lithographic crayons than anyone in the history of the medium.

When Menihan studied with Brown in 1934 and 1935, it is no exaggeration

to say that he was under the tutelage of the world's foremost expert

in lithography.

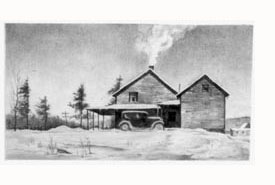

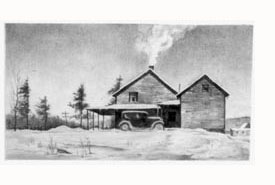

By

the mid 1930s, however, Brown was practically destitute. His modest

home, on Zena Road, two miles from Woodstock, had no electricity

or running water, and his studio, located behind the house, was

heated by a wood-burning stove. Brown was suffering from cancer

at the time, but he refused to go to a hospital, preferring instead

to spend his last years in familiar surroundings. By

the mid 1930s, however, Brown was practically destitute. His modest

home, on Zena Road, two miles from Woodstock, had no electricity

or running water, and his studio, located behind the house, was

heated by a wood-burning stove. Brown was suffering from cancer

at the time, but he refused to go to a hospital, preferring instead

to spend his last years in familiar surroundings.

Brown

sat in a fan-back wicker chair and instructed Menihan through chapter

after chapter of his book. While Menihan worked stones, Brown, whose

quest for knowledge was undiminshed, read Hacklet's Vogages, a history

of the world composed of original documents. Brown

sat in a fan-back wicker chair and instructed Menihan through chapter

after chapter of his book. While Menihan worked stones, Brown, whose

quest for knowledge was undiminshed, read Hacklet's Vogages, a history

of the world composed of original documents.  A

sign hanging in Brown's studio proclaimed, "Into the making of a

perfect work, time is an element that does not enter." A

sign hanging in Brown's studio proclaimed, "Into the making of a

perfect work, time is an element that does not enter."

Menihan

learned how to make his own grease crayons, a skill few lithographers

possessed, and he learned the intricacies of etching and printing

stones. He also learned, in no uncertain terms, the meaning of the

sign hanging in the studio. Menihan

learned how to make his own grease crayons, a skill few lithographers

possessed, and he learned the intricacies of etching and printing

stones. He also learned, in no uncertain terms, the meaning of the

sign hanging in the studio.

One

summer, when Menihan had finished his work, Brown asked him to separate

his lithographs into three piles: best, medium and discards. After

discussing the quality of the work, Brown asked Menihan what he

planned to do with the prints, and Menihan said he guessed he would

take them home. Brown struggled up out of his chair, hobbled over

to the prints, picked up the "discard" pile and, tossing the prints

into the flames of the wood-burning stove, said "This is what you

do with work that's not perfect." He then picked up the "medium" pile and tossed them, too, into the stove, leaving only the two

perfect prints. One

summer, when Menihan had finished his work, Brown asked him to separate

his lithographs into three piles: best, medium and discards. After

discussing the quality of the work, Brown asked Menihan what he

planned to do with the prints, and Menihan said he guessed he would

take them home. Brown struggled up out of his chair, hobbled over

to the prints, picked up the "discard" pile and, tossing the prints

into the flames of the wood-burning stove, said "This is what you

do with work that's not perfect." He then picked up the "medium" pile and tossed them, too, into the stove, leaving only the two

perfect prints.

Menihan

obivously learned his lesson well because his lithographs were meticulously

executed. Menihan

obivously learned his lesson well because his lithographs were meticulously

executed.  Over

the next two decades (1935-1955) Menihan produced more than 100

lithographs, each of them beautifully drawn and flawlessly printed.

At a time when many artists merely drew images on stone and hired

professionals to make the prints, Menihan did it all himself. Consequently,

his lithographs exemplify a wonderful union of content and technique. Over

the next two decades (1935-1955) Menihan produced more than 100

lithographs, each of them beautifully drawn and flawlessly printed.

At a time when many artists merely drew images on stone and hired

professionals to make the prints, Menihan did it all himself. Consequently,

his lithographs exemplify a wonderful union of content and technique.

Brown's

influence is evident in Menihan's early lithographs. In several

of them, Menihan outlined the composition with an unruled line in

a manner characteristic of Brown's work. In early prints, he also

used the expressive, autographic strokes that were all hallmark

of Brown's landscapes. As Menihan grew more confident in his own

style, these characteristics gave way to a subtle, continuous-tone

shading in combination with a strong line. Brown's

influence is evident in Menihan's early lithographs. In several

of them, Menihan outlined the composition with an unruled line in

a manner characteristic of Brown's work. In early prints, he also

used the expressive, autographic strokes that were all hallmark

of Brown's landscapes. As Menihan grew more confident in his own

style, these characteristics gave way to a subtle, continuous-tone

shading in combination with a strong line.

After

Brown's death, Menihan, who had studied business in college, helped

Brown's family with his artistic estate. Apparently in appreciation

for his help, Brown's family sent several packages of prints to

Menihan in the months that followed. In 1988 he and his wife, Margaret,

donated their collection of more that 50 of Brown's lithographs

to Rochester's art museum, the Memorial Art Gallery, endowing the

gallery with one of the most significant collections of Brown's

prints in the United States. After

Brown's death, Menihan, who had studied business in college, helped

Brown's family with his artistic estate. Apparently in appreciation

for his help, Brown's family sent several packages of prints to

Menihan in the months that followed. In 1988 he and his wife, Margaret,

donated their collection of more that 50 of Brown's lithographs

to Rochester's art museum, the Memorial Art Gallery, endowing the

gallery with one of the most significant collections of Brown's

prints in the United States.

Menihan's

NEA grant application also sheds light on his motivation and the

aesthetic ideals behind his lithographic career. His goal, he writes,

was to "produce a group of lithographs which would interpret the

life and thinking of the Northeastern section of the United States." Menihan's

NEA grant application also sheds light on his motivation and the

aesthetic ideals behind his lithographic career. His goal, he writes,

was to "produce a group of lithographs which would interpret the

life and thinking of the Northeastern section of the United States."

At

a time when many artistis of his generation were turning to the

various forms of abstraction in vogue in the 1940's, At

a time when many artistis of his generation were turning to the

various forms of abstraction in vogue in the 1940's,  Menihan

wrote of his impluse to deal in a representational manner with subjects "...intermixed with the course of my life, factories in which I

worked as a boy, cities in which I've studied, lake freighters,

county fairs, summer resorts, farm houses, tenements, and country

clubs." Menihan

wrote of his impluse to deal in a representational manner with subjects "...intermixed with the course of my life, factories in which I

worked as a boy, cities in which I've studied, lake freighters,

county fairs, summer resorts, farm houses, tenements, and country

clubs."

He

did not see his work as "photographic" documents but, rather as

expressions of character. One of the reasons he gives for employing

a print-making medium is the ability to "disperse among laymen the

benefits derived from possession of works of art." He

did not see his work as "photographic" documents but, rather as

expressions of character. One of the reasons he gives for employing

a print-making medium is the ability to "disperse among laymen the

benefits derived from possession of works of art."

Menihan's

characteristic modesty is apparent when he deals with the "presumable

significance" of his work: Menihan's

characteristic modesty is apparent when he deals with the "presumable

significance" of his work:

"It

can only be said that I bring to the project honesty, energy, a

degree of skill and love of my work...Whether or not the world will

choose to consider the result "significant art" is a matter I cannot

here decide." "It

can only be said that I bring to the project honesty, energy, a

degree of skill and love of my work...Whether or not the world will

choose to consider the result "significant art" is a matter I cannot

here decide."

Through

his long involvement with the Rochester Print Club, Menihan also

met and became friends with such printmakers as Albert Winslow Barker

and Norman Kent. Barker, who had also studied with Brown, shared

his lithographic technical research with Menihan in Rochester and

at his home in Moylan, Pennsylvania. Through

his long involvement with the Rochester Print Club, Menihan also

met and became friends with such printmakers as Albert Winslow Barker

and Norman Kent. Barker, who had also studied with Brown, shared

his lithographic technical research with Menihan in Rochester and

at his home in Moylan, Pennsylvania.

Kent

wrote about Menihan's lithographs in a 1945 article in American

Artist magazine, quoting the artist e Kent

wrote about Menihan's lithographs in a 1945 article in American

Artist magazine, quoting the artist e xtensively

during the peak of his lithographic activity. In the article, Menihan

discussed the unique properties of the lithographic drawing. xtensively

during the peak of his lithographic activity. In the article, Menihan

discussed the unique properties of the lithographic drawing.

"Experience

has shown me that because of the distinctive qualities of lithographic

stone as a drawing medium it is almost useless to develop final

drawings on paper, simply because no paper will provide the same

surface for work as a lithograhic stone. The stone itself is an

inspiration; it provides many effects which are especially "lithographic." Therefore, I adopted the practice of drawing the large preliminary

sketch right on stone, and pulling a proof or two, with the idea

of graining another stone for the final rendering." "Experience

has shown me that because of the distinctive qualities of lithographic

stone as a drawing medium it is almost useless to develop final

drawings on paper, simply because no paper will provide the same

surface for work as a lithograhic stone. The stone itself is an

inspiration; it provides many effects which are especially "lithographic." Therefore, I adopted the practice of drawing the large preliminary

sketch right on stone, and pulling a proof or two, with the idea

of graining another stone for the final rendering."

He

also discussed the reason he preferred to print his own stones at

a time when many artists simply drew on the stone and had a professional

printer pull the prints: "The service of these several excellent

lithographic printers are available, but to me drawing on a stone

and having someone else do the printing is comparable to owning

a new bathing suit, and have friends wear it in swimming." He

also discussed the reason he preferred to print his own stones at

a time when many artists simply drew on the stone and had a professional

printer pull the prints: "The service of these several excellent

lithographic printers are available, but to me drawing on a stone

and having someone else do the printing is comparable to owning

a new bathing suit, and have friends wear it in swimming."

Menihan's

knowledge of the crayon formulas, gleaned from Brown and Barker,

was especially helpful in making his lithographs distinctive. Menihan's

knowledge of the crayon formulas, gleaned from Brown and Barker,

was especially helpful in making his lithographs distinctive.

"Graphite

(as an ingredient in the crayon) is Albert Barker's idea and he

should have full credit for working it out. It has meant the difference

between nothing and a whole new technique to me, inasmuch as I have

made big chunks of crayon which do beautiful "grays" with one fell

swoop." "Graphite

(as an ingredient in the crayon) is Albert Barker's idea and he

should have full credit for working it out. It has meant the difference

between nothing and a whole new technique to me, inasmuch as I have

made big chunks of crayon which do beautiful "grays" with one fell

swoop."

Menihan's

enthusiasm for the vocabulary of lithography is indicative of an

artist who embraced a given medium and extracted from it all the

particular properties it was capable of yielding. The lithograhic

oeuvre of John Menihan embodies the ideal of art as a part of everyday

life, a chronicle of the perceptions and reactions of the artist

to the world around him. Menihan's

enthusiasm for the vocabulary of lithography is indicative of an

artist who embraced a given medium and extracted from it all the

particular properties it was capable of yielding. The lithograhic

oeuvre of John Menihan embodies the ideal of art as a part of everyday

life, a chronicle of the perceptions and reactions of the artist

to the world around him.

Ron Netsky is Chairman

of the Art Department

at

Nazereth College in Rochester, NY at

Nazereth College in Rochester, NY

|

by

Joseph Pennell, James A. McNeill Whistler and Robert Riggs spurred

his interest in the medium.

by

Joseph Pennell, James A. McNeill Whistler and Robert Riggs spurred

his interest in the medium.